Tags

Acetabulum, DePuy, Femur head, Femur neck, hip, Hip Replacement, joint replacement, Patient, surgery

Hip Joint Replacements

Source: patient.co.uk

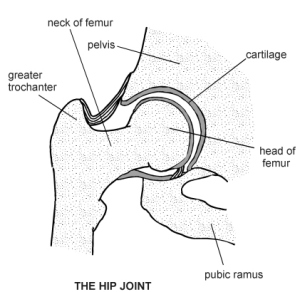

Hip joint replacement (hip arthroplasty) is the surgical replacement of all, or part, of the hip joint with an artificial device. It can allow considerable improvement in pain and disability for the patient and has become one of the most successful innovations in modern medicine.1

Hip joint replacement (hip arthroplasty) is the surgical replacement of all, or part, of the hip joint with an artificial device. It can allow considerable improvement in pain and disability for the patient and has become one of the most successful innovations in modern medicine.1

The procedure can be either a total hip arthroplasty or a hemiarthroplasty.2

- Total hip arthroplasty – the articular surfaces of the femur and the acetabulumare replaced. This can be:

- Conventional total hip arthroplasty – replacement of the femoral head and neck.

- Resurfacing total hip arthroplasty – replacement of the surface of the femoral head.

- Hemiarthroplasty – only the articular surface of the femoral head is replaced. This can be:

- Unipolar hemiarthroplasty – replacement of the femoral head and neck.

- Bipolar hemiarthroplasty – replacement of the femoral head and neck plus an addition of an acetabular cup that is not attached to the pelvis (i.e. fits into the existing acetabular cup).

- Resurfacing hemiarthroplasty – replacement of the surface of the femoral head.

Epidemiology

- Approximately 72,000 hip procedures were recorded in the National Joint Registry in 2007 (total for both the NHS and private sectors).3

- The number of hip replacements performed is rising annually.

- Assuming no change in the age and sex specific arthroplasty rates, the estimated number of hip replacements will increase by 40% over the next 30 years because of demographic change alone. The proportionate change will be substantially higher in men (51%) than women (33%), with a doubling of the number of male hip replacements in those aged over 85. Changes in the threshold for surgery may increase this further (by up to double the current number).4

Indications

- Total hip arthroplasty:

- Pain and disability due to degenerative or inflammatory arthritis in the hip joint, where non-operative management has failed and quality of life is being significantly interfered with.1

- Fracture of the proximal femur.

- A resurfacing total hip arthroplasty may be considered in a young person with osteoarthritis and good bone stock (the advantage is that the femoral neck is preserved which may be advantageous if a later conventional arthroplasty is needed).2

- Hemiarthroplasty – usually indicated for patients with a femoral neck fracture who meet the following criteria:5

- Poor general health or frailty.

- Pathological hip fracture.

- Severe osteoporosis.

- Inadequate closed reduction.

- Displaced fracture that is several days old.

- Pre-existing hip disease (e.g. rheumatoid arthritis, avascular necrosis).

- Neurological disease.

Some considerations

- It is essential to ascertain that the hip is the site of the pathology, as pain in the hip can originate from other sites such as the knee or back. Replacing a hip that is not the cause of the pain will be of no value.

- Total hip replacement should not be undertaken lightly in a younger patient, as they tend to wear out the prosthesis due to a longer and more active life. Revision is much more substantial than the primary operation.

- This surgery is often conducted on the elderly. They need a thorough assessment of fitness for operation, including the ability to complete the necessary postoperative rehabilitation. The operation can be conducted under regional rather than general anaesthetic but it is still a long and demanding procedure.

- Adequate quadriceps and other muscles around the joint are essential for rehabilitation. Poor muscles and neurological disease around the joint may be a contra-indication to surgery. The patient must be physically and mentally able to take part in rehabilitation.

When to refer to secondary care

- Most people with osteoarthritis of the hip are managed in primary care.

- The question is when to refer to an orthopaedic surgeon. (The need for immediate admission of a patient with a fractured hip is clear.)

- The British Orthopaedic Association suggests that local referral pathways should be drawn up giving criteria for referral.1

- Referral may be based on a locally developed explicit scoring system. This may take into account factors such as the extent to which the condition is causing pain, disability, sleeplessness, loss of independence, inability to undertake normal activities, reduced functional capacity or psychiatric illness.1

Preoperative care1

- A pre-admission assessment should take place within six weeks of the operation in secondary care.

- This should include identification of comorbidities and routine preoperative investigations. However, general health screening should be carried out by the GP before referral to secondary care.

- Information about the operation should be given to the patient, including risks and possible complications. Written supportive information should be given.

- Fully informed consent should be obtained.

- Provisional discharge planning should take place.

Choice of device and surgical technique

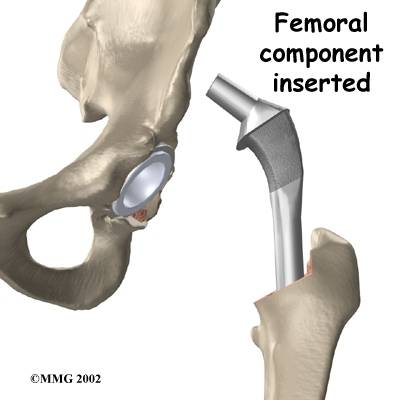

- There are many different types of device available for joint replacement surgery. Materials used include metal, polyethylene and ceramic.2 Various methods of fixation include polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) cement, screw fixation, cementless press fit and porous ingrowth fixation.2

- The simplest and most commonly used classification is whether prostheses are:6

- Cemented.

- Uncemented.

- Hybrid (a cemented stem with a cementless cup).

- The surgeon may have a preference for an individual implant depending on factors including their training and consultant colleagues’ preference.

- Patient factors including age and underlying health and comorbidities may also influence choice of device, e.g. ease of revision is needed in young patients.6

- Guidance exists from the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) about which prosthesis to use.6 NICE suggests that the best prostheses to be used are those that demonstrate a revision rate of 10% or less at 10 years.6

- Cemented prostheses: these are thought to make up 90-95% of the UK total hip replacement market. NICE supports and suggests their use.6 (Although some evidence exists that these guidelines are not being followed.)7 They tend to fix well and early mobilisation is usually possible. There is the possibility of a foreign body reaction to the cement, which can affect the surrounding bone.

- Uncemented prostheses: these are generally easier to revise (an advantage in younger people who may outlive the prosthesis) but may take longer to fix and full mobilisation/weight bearing is not possible as early.

- NICE also suggests that more evidence of the performance of hip prostheses over longer periods of follow-up is required.6 The National Joint Registry will help this.3

Metal-on-metal hip resurfacing arthroplasty

- In this procedure, the damaged surfaces of the femoral head and the acetabulum are removed and resurfaced: a metal cup in the acetabulum and a metal surface for the femoral head.

- The use of metal-on-metal articulations has the advantage that they wear less and that also the particles are smaller and cause less inflammation. A larger femoral head component may be used which may lead to fewer hip dislocations.2 Bone stock is also preserved, meaning revision procedures may be easier.

- BUT there have been some reports of metal ions being found in the blood and urine and a concern has been raised about an increased incidence of leukaemia.2 A working party has been set up as a collaboration between the British Orthopaedic Association, the British Hip Society, the National Joint Registry and the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency to look into this matter so that information can be built up to provide advice.8

- NICE issued guidance on this subject in 2002.9 They suggest that metal-on-metal hip resurfacing arthroplasty should be considered in people with advanced hip disease who would normally be given a conventional hip replacement but who are likely to outlive the joint replacement.

- NICE also stated that surgeons should inform patients that less is known about the medium- to long-term safety and reliability of this procedure. This uncertainty should be weighed against the potential benefits.9

Minimally invasive hip replacement surgery

- NICE supports the use of single mini-incision hip replacement. Fluoroscopic guidance and computer-assisted navigation tools may be used. Benefits may include less tissue trauma, less blood loss and less pain. Appropriate training of the clinician is required and data should be submitted to the National Joint Registry.10

- Guidance was also issued by NICE on minimally invasive two-incision surgery for total hip replacement. They confirm the procedure is safe but should be offered by suitably trained surgeons able to offer patients conventional hip replacements and with normal arrangements for clinical governance, consent and audit. Again data should be submitted to the National Joint Registry.11

Postoperative care and rehabilitation1

- Mobilisation postoperatively should include input from a physiotherapy team. Specific advice should be given to the patient about what they can and cannot do.

- Patients should only be discharged when they are considered capable of managing in the environment of their destination.

- Contact telephone numbers in case of problems should be provided.

- Patients should undergo outpatient follow-up within 8 weeks of the operation.

- Best practice minimum requirements for subsequent follow-up are at one, five and then each subsequent five years after operation. Clinical examination and X-rays should be carried out to assess for possible implant failure.

Complications

- Postoperative pain and constipation.

- Urinary tract infection or retention of urine: urinary catheterisation for the operation is routine and can lead to these.

- Thromboembolism: prophylaxis is routine but there is still a risk.

- Chest infection.

- Implant fracture.

- Dislocation of the hip: can occur at any stage but usually occurs early.

- Wound infection or dehiscence.

- Infection of the prosthesis: it may be necessary to remove the prosthesis.12

- Heterotopic ossification: usually asymptomatic but bony ankylosis can occur.2

- Mechanical loosening and failure of the prosthesis: can occur in the longer term; can present with pain.

- Particle disease: a foreign-body reaction to implant debris causes focal osteolysis.12

After hemiarthroplasty:5

- Fracture of the femur can occur.

- Painful hemiarthroplasty may require conversion to a total hip replacement.

Prognosis

- The clinical effectiveness of a prosthesis can be assessed by looking at:6

- The persistence of pain and immobility.

- The proportion of total hip replacements that require revision within a specific period.

- About 80% of people get a good result with improved mobility and loss of pain.

- The whole team, including surgeons, nurses, physiotherapists and occupational therapists contribute to the overall success of total hip replacement.6

- The 30-day mortality rate after elective total hip replacement is about 0.5%.13,14

- After an arthroplasty for a fractured hip, the 30-day mortality rate is 2.4%.15

- A 3% prevalence of prosthetic loosening is seen at 11 years.2

- There is a 1% prevalence of prosthetic infection.2

History of hip joint replacement

- In 1923, Dr. Marius Smith-Peterson of Massachusetts General Hospital used a glass cup to cover and reshape an arthritic femoral head. The original glass cup failed but it led to the development of similarly-shaped implants of strong and durable plastic, followed by metal materials. Subsequently, metallic femoral devices with anatomically-sized heads and variable femoral stems were developed.

- Many surgeons and bio-engineers contributed to the concepts, techniques and designs of implants for total hip replacement but the name most associated with early hip joint replacement is Sir John Charnley. He reported his experience with a steel femoral component and a plastic socket cup in 1961. He also revolutionised the field with the use of the self-curing acrylic cement used to fix the implants into the bone. These advances greatly improved the success rate of total hip replacement. The Charnley concepts of the hip implants are still in use today to a large extent. He came from Manchester, was born in 1911 and died in 1982.

- Dr Austin T Moore was an orthopaedic surgeon in South Carolina. He performed one of the first total hip replacements in 1940 but it was the hemiarthroplasty to which he lent his name. He first performed this in 1942. He was born in 1899 and died in 1963.

Document references

- Primary Total Hip Replacement: A Guide to Best Practice, British Orthopaedic Association (2006)

- Jacobson JA, Hip Replacement, eMedicine, Mar 2009

- National Joint Registry, National register of prosthetic joints

- Birrell F, Johnell O, Silman A; Projecting the need for hip replacement over the next three decades: influence of changing demography and threshold for surgery.; Ann Rheum Dis. 1999 Sep;58(9):569-72. [abstract]

- Hemiarthroplasty of the Hip, Wheeless’ Textbook of Orthopaedics

- Hip disease – replacement prostheses, NICE (2000)

- Roberts VI, Esler CN, Harper WM; What impact have NICE guidelines had on the trends of hip arthroplasty since their publication? The results from the Trent Regional Arthroplasty Study between 1990 and 2005. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007 Jul;89(7):864-7. [abstract]

- British Orthopaedic Association, Metal on metal articulation in hip surgery, June 2008

- Hip disease – metal on metal hip resurfacing, NICE (2002)

- Single mini-incision surgery for total hip replacement, NICE (2006)

- Minimally invasive total hip replacement, NICE Interventional Procedure Guideline (October 2010)

- Tigges S, Stiles RG, Roberson JR; Appearance of septic hip prostheses on plain radiographs.; AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1994 Aug;163(2):377-80. [abstract]

- Lie SA, Engesaeter LB, Havelin LI, et al; Early postoperative mortality after 67,548 total hip replacements: causes of death and thromboprophylaxis in 68 hospitals in Norway from 1987 to 1999. Acta Orthop Scand. 2002 Aug;73(4):392-9. [abstract]

- Mahomed NN, Barrett JA, Katz JN, et al; Rates and outcomes of primary and revision total hip replacement in the United States medicare population. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003 Jan;85-A(1):27-32. [abstract]

- Parvizi J, Ereth MH, Lewallen DG; Thirty-day mortality following hip arthroplasty for acute fracture.; J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004 Sep;86-A(9):1983-8. [abstract]

Acknowledgements

Document ID: 1623

Document Version: 25

Document Reference: bgp24707

Last Updated: 23 Feb 2011

Planned Review: 22 Feb 2014

The authors and editors of this article are employed to create accurate and up to date content reflecting reliable research evidence, guidance and best clinical practice. They are free from any commercial conflicts of interest. Find out more about updating.

Related articles

- Future of Hip replacement may include more resurfacing, percutaneous fixation (earlsview.com)

- AVN Avascular Necrosis or ON Osteonecrosis (earlsview.com)

- Ceramic Hip Joint Replacement Devices (earlsview.com)

- Minimally Invasive Total Hip Arthroplasty (earlsview.com)

- Anterior Hip Replacement (earlsview.com)

- Cementless Implants Tied to Improved Hip Implant Survival (earlsview.com)

- Techniques In Implementing A Hip Replacement Operation (earlsview.com)

- Age, surgery type, coronary artery disease associated with complications after TKA (earlsview.com)

- Squeaking Ceramic Hips – Why? (earlsview.com)

- Radiographic Assessment of the Patient With a Total Hip Replacement (earlsview.com)

Pingback: Hip Replacement – UK ARC Patient Advice Booklet « Earl's View

Pingback: Rowing on the St. Joe River after hip replacement surgery « Earl's View

Pingback: British Orthopaedic Association PRIMARY TOTAL HIP REPLACEMENT: A GUIDE TO GOOD PRACTICE « Earl's View

Pingback: Arthritis New Zealand urges calm over replacement hip withdrawal « Earl's View

Pingback: WOW – femoroacetabular arthroscopy, more commonly known as hip preservation surgery … « Earl's View

Pingback: Hip Dysplasia – all you didn’t want to know! « Earl's View

Pingback: Hypertensive Patients Show Delayed Wound Healing following Total Hip Arthroplasty « Earl's View

Pingback: Total Hip Replacement in the Dysplastic Hip: The Use of Cementless Acetabular Components « Earl's View

Pingback: Developmental dysplasia of the hip « Earl's View

Pingback: New Zealand – Patient “J’s” 7 years of HELL story – ACC Legislation shelters those to blame « Earl's View

Pingback: New Zealand – Jill Cleggett’s 7 years of HELL story – ACC Legislation shelters those to blame « Earl's View

Pingback: Relief Trip to Nicaragua – Orthopedic surgeon Dr. Gerard Engh leads humanitarian effort « Earl's View

Pingback: Nigeria: Abuja Residents Throng Indian Hospital for Medicare « Earl's View

Pingback: UK – Answers to commonly asked questions from patients with metal-on-metal hip replacements / resurfacings « Earl's View

Pingback: Reverse shoulder arthroplasty has given new hope to patients suffering from severe arthritis « Earl's View

Pingback: New Hips Gone Awry Expose U.S. Kickbacks in Doctors’ Conflicts « Earl's View

Pingback: Hip Implants – from American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons « Earl's View

Pingback: Hip Replacement Loosening « Earl's View

Pingback: Hip Dislocation « Earl's View

Pingback: New Zealand – Patient J’s 7 years of HELL story – ACC Legislation shelters those to blame « Earl's View

Pingback: The problem of osteoporotic hip fracture in Australia « Earl's View

Pingback: Coloarticular fistula: A rare complication of revision total hip arthroplasty « Earl's View

Pingback: Hip revision surgery « Earl's View

Pingback: Length of stay following Total Hip Repalcement multifactorial, study finds « Earl's View

Pingback: Obesity a significant risk factor in complication rates following THA « Earl's View

Pingback: Septic Hip – Infection of the hip joint in children « Earl's View

Pingback: Femoral Osteotomy – commonly used for adults in the treatment of hip fracture nonunions and malunions « Earl's View

Pingback: Femoral Osteotomy Treatment & Management « Earl's View

Pingback: THA after intertrochanteric osteotomy results in higher complication rates, lower long-term prosthesis survival rates « Earl's View

Pingback: Leg length may be affected by use of spinal anesthesia during THR « Earl's View

Pingback: Hip Repalcement – Anterior Approach Gives Patients Another Option « Earl's View

Pingback: Earl – Three Days Until Hip Revision Day « Earl's View

Pingback: Earl – ONE DAY Until Hip Revision Day « Earl's View

Pingback: Women most at risk from metal-on-metal hip devices, National Joint Registry Annual Report finds « Earl's View

Pingback: UK – Impressive patient treatment – at Lynn’s Queen Elizabeth Hospital « Earl's View

Pingback: Supervised Exercise With Hip Osteoarthritis Allows Patients to Delay Total Hip Replacement « Earl's View

Pingback: Exactech Introduces New Material, Efficient Approach for Acetabular Reconstruction « Earl's View

Pingback: Fast Track Hip Replacement – Study by Dr Bryan Nestor « Earl's View

Pingback: Fast Track Hip Replacement – Study by Dr Bryan Nestor « Earl's View

Pingback: Study: Two-day Discharge After Arthroplasty Feasible « Earl's View

Pingback: Total Hip Replacement – Short Review « Earl's View

Pingback: Hinge knee prostheses yield pain relief, good stability and functional outcome « Earl's View